By Shirin Mazdeyasna, 08/23/2016. On Aug 13, we attended a local monastic festival and witnessed a beautiful ceremony of first having the site purified of obstacles. Then in the second part of the ritual having offerings in the honor of Padmasambhava by each one of the companions.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_btEWgZ1JGg]

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J4X-zcVY2DA]

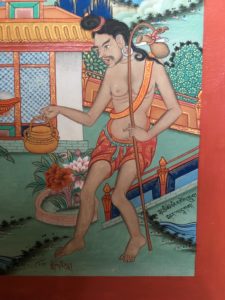

The most remarkable sacred art that we saw in Ladakh was at Alchi Monastery. Alchi Monasteries have the oldest surviving paintings in Ladakh and are famous for the special wall paintings and terracotta sculptures.

The reason for the survival of such old paintings, from 11th century, is for the dry and cold weather in Ladakh. The complex also had stupas that you could walk through and look up at the mandala structure above and find detailed wall paintings.

The Manjushri temple had a huge terracotta statue in the center with 4 families of the Buddhas on each side and one in the center. In the Lotsa temple, the style of the paintings was different from what previously we had seen in other monasteries, meaning there was a clear influence from Indo-Buddhist art. The influence was seen in the robes the buddhas were wearing, the style and structure of their faces, and how their bodies were shaded.

The artists of this murals had to be very careful of the proportions of the buddhas, as they were an image people would meditate on and use in their spiritual practice. The artists were mostly anonymous and most religious art were to be done for commissions of creating good karma. The art is made not for fame, meaning it will either be on the walls working as visual dharma, or it will be destroyed (sand mandalas) or put in stupas.

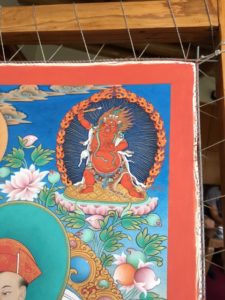

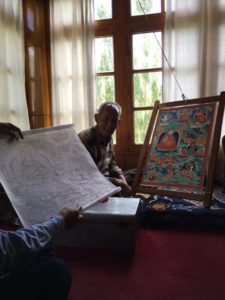

Talking about sacred art artists, we had the rare opportunity of meeting a traditional thangka painter at his local home in Ladakh.

He graciously explained his process of stringing the cotton canvas to the frame, gessoing the surface with a special material, and then working on a grid for the painting. The proportions has to be perfect, otherwise it will cause bad karma for the artist. The best paint is from natural powders and what he actually uses.

After he’s done with a painting or series of paintings, he would then create the proper silk cover on the front, rooting from Tibet’s nomadic culture, for the convenient of display and transportation.

For this series that he was currently working on, he was commissioned by a Frenchman, whom followed the kagyu school of buddhism.

As the Buddhist Vajrayana practitioner (esoteric path of Buddhism) uses a thangka image for a point of reference/focus and guide in his mediation, he visualizes himself as being the center deity to further internalize the Buddha qualities. For such reason, the artist has absolutely no flexibility in creating the imagery (besides the small details of flowers and background clouds) and has to follow the existing scripts.

The thangka painters used to not sign their names on the paintings, as they only painted thangkas not for fame and money, but for their religious obsession, creating good karma, and spiritual practice while painting. However, only recently they have been mandated to put their names on their paintings.

Another fascinating fact is that the artist does not put a price on the series of paintings but they accept whatever the client pays. If the artist fixes a price, he’s not purely doing it for religious practices.

The artist has signed his name on the bottom right corner of the painting.

On the last evening of being in Ladakh, we had the honor of visiting our host’s local house. The mother of the family graciously greeted us with butter tea and homemade Ladakhi cookies, as well as freshly picked apricots from their garden. This visit was extra special for me because the host were a muslim family and I got a chance to ask them questions about their practice, as well as communicate with them with the similar written languages of Farsi and Urdu.

The structure and interior of their house was made all by local wood and very delicate Ladakhi tradition of craftsmanship -all handmade.

The harmony of architecture and nature in Ladakh was indeed one of a kind. From how houses and monasteries were build in the valleys and along the mountains, to the interior of structures all made by hand and from the local resources.

During our last days in Ladakh, we visited a farm house close to Shanti Stupa, in the outskirt of Leh’s green valley. The building on the property was build from local materials, expect for the glass that had been imported. Taking out the glass, they could recycle and rebuild the house by only using materials from the property.

Also, the food that we were served for dinner, breakfast, and lunch was all provided locally from the farm, with the exception of sugar and rice (that could not be harvest there due to the high altitude).

Early in the morning during our stay in the farm, the 4 of us made a hike up to the valleys and saw a herd of yaks feeding on the grass grown on the riverside, and a herd of bharals (Himalayan blue sheeps) running across the valley with phenomenal natural camouflage with the mountains.