By Isabella Kazanecki, 07/22/2017. On the last leg of our train ride to Varanasi (hour 12) I got my first glimpse of the Ganga. It was a reassuring feeling that my remote fascination had been realized into something truly great. I intended to come to Varanasi to spend time with the Sankat Mochan Foundation after seeing all the work they had presented on their website. I had gotten a government perspective on the Ganga from the Centre for Science and Environment in New Delhi, and now I wanted to see what grassroots organizations were doing on the ground. So once we arrived, my travel companion, Zoya, and I started a journey from Pandey Ghat, where our hostel is, to Tulsi Ghat, where the foundation’s headquarters lie; dodging shouts from boat drivers and making risky climbs to avoid flooded areas. We even balanced on a two inch wide ledge, about eight feet above the toxic Ganga. When we finally arrived, we found the place deserted and dusty. Only a chalkboard meant to chart water quality, but left unfilled in, and a life size paper tree in a dusty old room.

We even asked a local man what had happened and he told us to return in four hours. When we returned we again were told by a random man to return in two hours. After that time, there was no one around to even ask. It was frustrating and disturbing and I felt that my trip had been for nothing. But as I sulked back to my hostel, I realized I had learned something from this failure. Along the way to this non-existent water project we had picked up a friend we ran into on one of the ghats along the river, a man sang two Hindu songs to us (free of charge) as his son played with our straw hat, we witnessed people ceremoniously bathing, children fishing, young swim teams diving and doing cannonballs into the river, devotees praying, teachers teaching, skilled old men fixing ancient boats, and women washing which transforms the landscape into a maze of flowing colorful blankets, scarves and sarees along with the rhythm of banging the wet fabric against rocks to dry. We slid down walls when there were no stairs, we looked at murals painted along the ghats, and I learned how to play the ukulele. I didn’t need to interview someone from an Australian sponsored institution to hear the story of the Ganga because the Ganga could speak for herself.

The river is truly a mother. She produces life and is the center of all activity in the city. Everything comes back to the Ganga and one lives in full awareness of it. This is really how my interest began in this river. I began by taking a class with Dr. Pasang Sherpa, a post doc fellow here at the New School, about Kailas mountain. It made me start to think about how one’s landscape affects one’s life. For example, in New York, one lives looking up, but also feeling small. Here, the Ganga is omnipresent and bursting with life despite its dramatically low oxygen levels and high fecal content.

These daily interactions are a quotidian choreography. I see dance as a chain of relationships and exchanges between bodies and space, therefore Varanasi is a city that dances. Especially when I witness poojas, or ceremonies, I can’t help my excitement at the exchanges of energy among all the bodies in such a sacred space. In addition to this, I trained in Martha Graham technique who is known for her ritualistic repertoire. Ceremony and ritual is comforting to me because of the way that pieces come together like cogs in a machine to produce something reverent and beautiful. A specific piece of Martha Graham’s like this is Rite of Spring, choreographed to Aaron Copland’s famous score. One night, myself along with some friends went to a ceremony in the Golden Temple.

We stood in two lines facing each other with a walkway in the middle in front of a room in the center of the temple. A young boy in the room lit a plate of candles while the Holy Man kneeled. While this was happening young boys fiercely played damaru drums, which are two headed drums designed for shaking really fast, and others rang loud bells. It was chaotic and disorienting and at first I was afraid but at some point I found my headspace in all the intensity and was then overwhelmed with admiration for what I was so privileged to be witnessing. The fire was then taken out of the room and people placed their hands over it and directed the energy to their face before we walked processionally around the temple. I felt that for a tiny moment, I was a part of an ancient dance older than Christianity, older than my nation, older than I could even imagine. I was allowed into this world for a brief respite; everyone was caught up in each other’s shared energy. In addition to this ceremony we attended nightly poojas and even had the good fortune to be able to witness the traditional burning of bodies along the Ganga. We always watched from a distance, but it was still humbling to be in the presence of such a deeply rooted tradition as well as those passed. Both events are powerful and an intense experience. I didn’t want to be overly intrusive but this is a picture from the boat view of one of these ceremonies. The smoke, fire, loud chanting, and young children hopping from boat to boat selling offerings with a fierce business mind can be overwhelming but I was in complete admiration of the rhythmic chaos as well as the deep connection that was being oiled and strengthened by these actions as it does every hour of every day. This lasted until I questioned the fact that women were not allowed at the funeral because they are too emotional and may throw themselves onto the fire out of desperation, when I was kindly chased away.

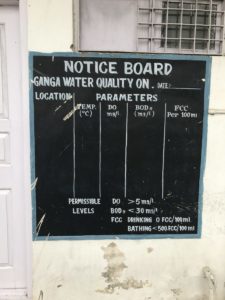

In regards to the pollution of Ganga, I found mostly bad news. I found remnants of a movement to clean Ganga but no real action or progress. I saw murals, signs, and adverts acknowledging the crisis, such as the picture above but not visible actions. The most devastating and awe inspiring moment was when I happened upon Nagwa Nalla, which is upstream of the main city. Nagwa Nalla used to be called Assi River but it was renamed because, as Sunita Narain writes, rivers without water are drains; and this drain flows directly into the Ganga. The Nagwa drain has a BOD load of 4,000 kg per day, placing right above the Varuna drain at 3,888 kg per day. Essentially, BOD load is used to express the quantity of wastewater passing into a waste treatment center or body of water and the greater this number is, the greater the levels of pollution. Wastewater contains contaminants such as carbohydrates, proteins, oils, and fats which are degradable by oxygen. BOD is an acronym for bio degradable oxygen demand therefore this measurement tells the amount of sewage in relation to the demand of oxygen required to break down and treat that water. I looked at Nagwa Nalla from the main road, which is a bit raised from the river so there is a railing that separates the two. I couldn’t help but gaze in awe of the massive heaps of garbage and waterfalls of toxic sewage as if it were the Taj Mahal. As of January 30th of this year, the fecal coliform count at Nagwa is 4,100,000/100 ml. Every day, Varanasi produces 233 million litres of sewage per day but only 25% of that is able to be treated by the city’s three sewage treatment plants (STP) and the remaining 75% is discharged without treatment into the Ganga river. This is assuming all three centers are functioning which they rarely are. The main STP is Dinapur, following that is Diesel Locomotive Works, and Bhagwanpur.

Varanasi sources 38% of its water from the Ganga and the rest comes from 220 tube wells that pump groundwater which is managed by the organization called Jal Nigam. Jal Nigam is led by a chairman appointed by the state government and is a product of the 1975 Water Supply and Sewage Act. However this supply only covers 69% of Varanasi’s properties, leaving out Varanasi’s poorer areas, of which 42% is covered. The remaining 58% of poor areas rely on hand pumps as opposed to taps, such as the one in the picture to the left. Regardless of the method of extraction, groundwater is hardly better than that of the Ganga. Household as well as industrial waste is disposed of in low lying areas of the city and easily contaminates groundwater which travels through cracked and penetrable pipes. It seems that here there is a similar distrust of distribution networks, just as Dr. Mahreen Matto of New Delhi’s CSE Water Team had. This is another case in which decentralized water systems would prove resourceful.

Nevertheless, of course I was always carrying a giant water bottle in my hand and went through multiple a day. It occurred to me that packaged water companies are soaring in these hard times when a local that I befriended made a comment about the packaged water company. The bottles are not the typical Poland Spring, Aquafina, and Fiji that we know so well, but actually smaller names like Drop, King Kool, and other odd off brand types. Basically it seems like bottled water is the temporary fix to fill the void created by government failure to address basic services but it is this mass consumption of bottled water that adds to the problem. Probably more on that later…

I’d like to close in a crude vignette of me crashing around in a rickshaw on a bumpy road drinking one of these off brand water bottles and deciding to take a closer look at the wrapping, only to see “Save Ganga!” scrawled along the heading. I know, ironic right?