US sanctions have hobbled Iran’s response to the pandemic writes Djavad Salehi‐Isfahani in an article originally published in Pandemic Discourses.

US sanctions have hobbled Iran’s response to the pandemic writes Djavad Salehi‐Isfahani in an article originally published in Pandemic Discourses.

In March 2020, Iran became the epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic outside China. In late February, after hushing up the news of the arrival of the virus, the government admitted to two deaths from the disease in the holy city of Qom. However, by then the pandemic had spread to other parts of the country. Suddenly, Iran’s leaders found themselves fighting on two separate fronts: one to save the economy from US sanctions and the other to save lives and the economy from the pandemic.

Iran was barely coping with challenges from US President Donald Trump’s “maximum pressure” campaign. In May 2018, the Trump administration withdrew the US from the Iran nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), and imposed the harshest sanctions ever imposed on a country. Since then Iran’s economy has been in a tailspin. Oil exports nosedived and the currency lost two-thirds of its value, triggering rapid inflation and general macroeconomic chaos. Iran was totally unprepared for Trump’s election and his determination to undo Barack Obama’s singular foreign policy achievement with the JCPOA.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration and its allies in the Persian Gulf and Israel have been waiting anxiously for more than two years for sanctions to bear fruit, expecting a collapsing economy followed by rising social unrest to force Iran’s leaders to capitulate. Their anxiety is justified. A disastrous US record of military intervention in the Middle East—in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and Syria—has made Trump, himself a critic of these military interventions, come to see a win without war as the only way for the US to assert its hegemony in the region.

“Rather than easing sanctions to help Iran manage the pandemic better, if only to stop the spread of the virus in the region, the US piled on more sanctions, and chose to ignore calls from world leaders, former U.S. diplomats, and the United Nations to ease sanctions.”

The Pandemic

Then came the pandemic, which caught Iran at its weakest economic state since the end of the war with Iraq three decades ago. Since US’s withdrawal from JCPOA in 2018, Iran’s GDP has declined by 11% and average living standards (measured by real household per capita expenditure) have declined by 13%. This deterioration is easy to trace to the maximum pressure campaign because in 2016, when the JCPOA was in partial operation and sanctions had eased, the economy grew by 13%. The sanctions cut oil exports, thereby reducing the supply of foreign exchange, which caused the currency to collapse and inflation to run rampant (in 2019 prices rose by 41%).

More importantly, the loss of oil exports, which in the past accounted for about half of government revenues, tied the government’s hands in any economic rescue effort. As in the rest of the world, the pandemic had disrupted production and put millions out of work in Iran, but, unlike in richer countries, its government lacked the resources to help its people weather the pandemic.

Rather than easing sanctions to help Iran manage the pandemic better, if only to stop the spread of the virus in the region, the US piled on more sanctions, and chose to ignore calls from world leaders, former U.S. diplomats, and the United Nations to ease sanctions. The thinking behind a tougher stance on Iran was summed up in a March 2020 Wall Street Journal editorial titled, “No Time to End Iran Sanctions.”

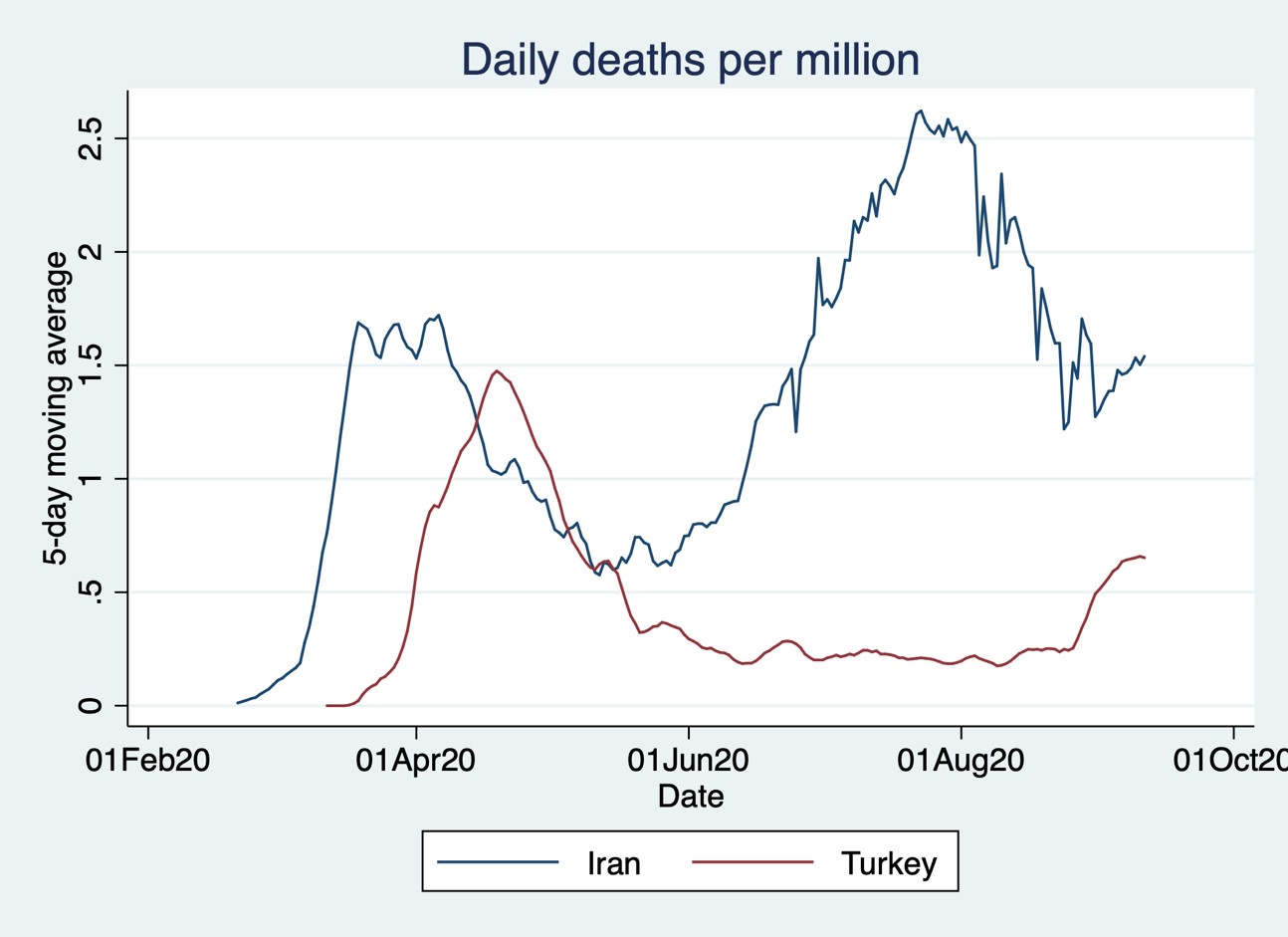

Despite a shortage of medical supplies, however, between April and May 2020 Iran was able to cut the number of daily deaths by half, avoiding the humanitarian disaster that many had predicted. As the graph below shows, within weeks Iran was able to bring down the fatality rate from COVID-19 from about 1.6 per million per day to about 0.6. The rate stayed low for about a month before the economic cost started to rise, forcing the government in Iran to reconsider its social distancing measures. As far as deaths are concerned, the first wave of the pandemic in Iran and Turkey were quite similar, as death rates first increased as cases mounted and the health system came under pressure and then declined. However, Iran’s experience diverged and a second wave hit the country in late May, whereas so far Turkey appears to have avoided a fierce resurgence (more on this below).

Five-day moving averages of the number of deaths per million. (Source: Author’s calculation based on WHO data compiled by Our World in Data; accessed 9/16/2020)

Employment figures for spring 2020 show that, compared to a year ago, 1.4 million fewer people worked and 2 million fewer were in the labor force. Even before the data came out, the government had decided that it had to end its social distancing regulations because it was unable to protect the incomes of those being laid off; or prevent an increasing number of lower-income families from falling into poverty.

Poverty and Social Protection

Revolutionary Iran has been relatively successful in keeping poverty low. It has an assortment of charities, large and small, as well as a welfare ministry that provides income assistance for about 10% of the population. Since 2011, the country has also had a universal cash transfer program initiated by the populist President Ahmadinejad that reached more than 70 million people with monthly cash deposits. The program was single-handedly responsible for keeping the poverty rate below 10% after the intensification of sanctions in 2012. The current neoliberal government of President Hassan Rouhani, which opposed cash transfers, allowed their value to decline with inflation so that by the time the pandemic hit, the real value of the cash transfers had declined to less than one-fourth of their value in 2011. As a result, during the last two years, the poverty rate has increased from 11% to 16% of the total population, adding another 3.7 million people to the poverty roll.[1]

The pandemic appears to have added to the misery. Data for the last month of the Iranian year 1398 (21 March 2019 to 20 March 2020), shows that real per capita household expenditure fell on average by an unprecedented one-third in the first month after COVID-19’s arrival in Iran, three times faster than for the year as a whole.

It is worth noting that in addition to income assistance, Iran has a fairly extensive health insurance program, which prevents the public health crisis from sending millions more into poverty. About 90% of rural and 75% of urban residents are covered by some form of government subsidized health insurance.

More financial assistance is on its way thanks to another of former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s redistributive schemes, known as “Justice Shares.” In 2007, he distributed shares of public companies to 49 million lower and middle-income individuals, which they were not allowed to sell until now. The current value or each justice share is about six months’ worth of the minimum wage, which can help a low-income family of four to survive for about a year (at this time they can only cash 60% of the value of the shares). For many who choose to sell their shares this is only a one-time solution.

“Given that Iran had shown that it can flatten the curve like other countries by shutting down the economy, it is not entirely unrealistic to conclude that had sanctions eased when the pandemic hit Iran, thousands of Iranian lives could have been saved.”

The Second Wave

Iran was one of the first countries to open its economy back up to avoid bankruptcy and economic catastrophe, and, predictably, by mid-May fatalities were climbing back up. The second wave has so far proven more deadly than the first. The contrast with neighboring Turkey, which has very similar health indicators to Iran (in 2019 life expectancy was 77 years in Turkey vs 76 in Iran and their HDI values were, respectively, 0.81. and 0.80), is instructive. It provides a rough idea of the human cost of the sanctions. Assuming that Iran could have followed the path of Turkey after mid-May, when the fatality rates of the two countries started to diverge, about 13,000 deaths might have been avoided. Given that Iran had shown that it can flatten the curve like other countries by shutting down the economy, it is not entirely unrealistic to conclude that had sanctions eased when the pandemic hit Iran, thousands of Iranian lives could have been saved.

Many critics of the Islamic Republic insist that Iran is hiding the real coronavirus death toll. If that is the case, the 13,000 death toll from sanctions is an under-estimate. Interestingly, Iran’s own death registration data (link in Persian) confirm the undercounting of fatalities due to COVID-19. Estimates based on the number of excess deaths during the winter and spring quarters of this year compared to the same quarters in the preceding two years are 4,800 and 19,300, for a total of 25,100 excess deaths. During the same period Iran reported 9,392 fatalities to WHO (the data depicted in the above graph). Extrapolation based on this difference (2.7 times) jives well with the higher number of deaths in a leaked document, which led the BBC to decry a coverup. If Iran was trying to cover up its deaths due to coronavirus, it was doing it very badly.

To put Iran’s fatality rates in perspective, adjusted for population size, it is much higher than Iran’s neighbors but lower than the rate in the more advanced countries like the US and Sweden.

Although the early predictions that the virus would kill between 250,000 and 500,000 Iranians by August 2020 have failed to materialize, and the second wave is slowly flattening, Iran is by no means out of the woods. Its economy is still in tatters, its currency is depreciating, and inflation is still above 30%. Given how far apart the positions of Iran’s leaders and the Trump administration are, there is little hope for any improvement in the near future. The situation could change significantly if the Democrats win the White House in November and decide to return the US to the JCPOA. It is ironic how intertwined the lives of ordinary Iranians with US politics is given how hard the Islamic Republic has tried to distance itself from the US over the past four decades.

Djavad Salehi‐Isfahani is Professor of Economics at Virginia Tech. He is also a Non-resident Senior Fellow at the Global Economy and Development, the Brookings Institution, a research affiliate of the Middle East Initiative at the Belfer Center, Harvard Kennedy School, and a Research Fellow at the Economic Research Forum (ERF) in Cairo, Egypt.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] For poverty rates after the cash transfer program, see Atamanov, A., Mostafavi, M. H., Salehi-Isfahani, D., & Vishwanath, T. (2016). Constructing robust poverty trends in the Islamic Republic of Iran: 2008–14. The World Bank. They use the World Bank poverty line of $5.50 in Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) for upper middle-income countries. I have used a similar poverty line to calculate the poverty rate for more recent years.