The Indian public health response to COVID-19 has been sidelining expert advice and scientific debate in favor of a political agenda. This article was originally published in Pandemic Discourses.

Experts have always played an important role in determining state responses to health crises. The Indian government’s policies for COVID-19 tell a story of how public health experts have been sidelined alongside a stifling of open scientific debate.

During the early stages of the pandemic, evidence based on epidemiological modeling of mortality due to COVID-19 created a panic and shaped the response of many countries. However, several scientists questioned the assumptions made in modeling exercises and argued that given the uncertainties of scientific and epidemiological information on the novel Corona virus, governments needed to calibrate policy responses. Notwithstanding this debate, India was among the few countries that opted for a severe lockdown, imposed in great haste with little debate on its process and consequences.

Even prior to the lockdown, there was little engagement between the government, individual experts, and public health institutions. For instance, the airlifting of Indian students from Wuhan, China in early February 2020, when the pandemic was peaking there, was driven by political and not public health criteria. That decision was announced by the Foreign Minister with little involvement of the health ministry or public health experts. Prior to the students return, there was already sufficient global evidence indicating that air travel was an important mode of transmission. While the students were quarantined on arrival, in general there was little effort to screen and trace passengers arriving in the country. The travel advisory issued after the reporting of the first positive case in Kerala put the onus on State governments to monitor those who had arrived from abroad for symptoms and implement the proper quarantine measures. What one can read from the Indian travel advisories issued in February and March 2020 is that they were not well informed by a public health understanding. A report from the Scroll.in states, “The government’s travel advisories between February 26 and March 16 suggest a hesitant expansion of airport screening and quarantining of passengers travelling from overseas. This is strange given the government’s very minimal testing regime was entirely foreign-travel linked.” (The Scroll.in, March 29th 2020)

The time lag in addressing public health measures was seen vividly during March 2020 as cases and deaths were rising while testing kits and protective equipment were in short supply. The need for increasing testing capacity became clear by the third week of March during the severe lockdown when the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) was entrusted with procuring the testing kits. However, there were inordinate delays in the procurement of the testing supplies because they had to be imported from China. A report in the Huffington Post describes the many delays after the Indian government’s decision to pursue mass testing. As the report observes:

Apart from seeking medical advice, the government made scant effort towards involving other experts including social scientists who could have helped assess the human dimensions of the lockdown measures and its economic consequences for the laboring population. The decision to go in for a draconian lockdown and broadcast public health messages that evoked fear among the population suggests that the government had a politically guided response that was not guided by a wide range of experts barring a few loyalist administrators.

What is clear is that the government had not built an ecosystem of varying expert opinions, but relied on ICMR, which is an apex medical research organization that focuses on communicable and non-communicable diseases in addition to drug and vaccine development. ICMR is certainly not in the business of implementing public health measures, unlike other institutions such as the National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) which has experience coordinating public health responses with state governments. During the initial period of the pandemic, there was little role for NCDC and even the Ministry of Health because all major decisions were coordinated between the Ministry of Home Affairs and the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO). Apart from seeking medical advice, the government made scant effort towards involving other experts including social scientists who could have helped assess the human dimensions of the lockdown measures and its economic consequences for the laboring population. The decision to go in for a draconian lockdown and broadcast public health messages that evoked fear among the population suggests that the government had a politically guided response that was not guided by a wide range of experts barring a few loyalist administrators. The communication of the uncertainties of the Pandemic and explaining the need for cooperation at the individual and community levels were not part of the political agenda. In fact, there was no role for public health experts to issue daily bulletins regarding the pandemic and how to manage it. Instead the Prime Minister chose to address the nation and gave the impression that everything would be centrally managed. The reality was that the responsibility of managing the pandemic was shifted to the state and local governments. In many places, as in the case of New Delhi, there were multiple authorities that worked at cross-purposes, resulting in a governance deficit. The messages communicated in Prime Minister Modi’s speeches were weak and did not help to build trust nor clear confusions in the minds of people.

As early as March 25th 2020, three important public health related associations – Indian Public Health Association, Association of Preventive and Social Medicine, and Association of Epidemiologists issued a statement opposing the draconian lockdown. They opined that:

“[India’s] draconian lockdown is presumably in response to a modeling exercise from an influential institution which was a ‘worst-case simulation.’ … Subsequent events have proved that the predictions of this model were way off the mark. Had the Government of India consulted epidemiologists who had better grasp of disease transmission dynamics compared to modelers, it would have perhaps been better served. From the limited information available in the public domain, it seems that clinicians and academics with limited field training and skills primarily advised the government. Policy makers apparently relied overwhelmingly on general administrative bureaucrats. The engagement with expert technocrats in the areas of epidemiology, public health, preventive medicine and social scientists was limited. India is paying a heavy price both in terms of humanitarian crisis and disease spread. The incoherent and often rapidly shifting strategies and policies especially at the national level are more a reflection of ‘afterthought’ and ‘catching up’ phenomenon on part of the policy makers rather than a well thought cogent strategy with an epidemiologic basis.”

Public health expertise was not sufficiently drawn upon by the Central government as it formulated the important elements for containing contagion such as providing for testing, protective equipment for frontline workers, active surveillance, contact tracing and the required infrastructure for hospitals to deal with severe cases of COVID-19.

Public health expertise was not sufficiently drawn upon by the Central government as it formulated the important elements for containing contagion such as providing for testing, protective equipment for frontline workers, active surveillance, contact tracing and the required infrastructure for hospitals to deal with severe cases of COVID-19. The selective choice of expertise was evident since it was essentially the Ministry of Home Affairs and the Prime Minister’s Office taking decisions without adequate consultation with public health experts, social scientists and clinicians. Among experts, it was medical specialists who were privileged; doctors from the All India Institute of Medical Science (AIIMS) who headed important clinical and research positions in key institutions such as Niti Ayog, ICMR, and AIIMS were relied upon. A high-powered technical committee was set up in March 2020 comprising of medical specialists from AIIMS, ICMR and Niti Ayog. The other representatives were Director of the National Centre for Disease Control, Director of the Infectious Diseases Centre, Secretary, Ministry of Health and the Chief Secretary of Kerala. Given the opacity of the workings within the PMO, it is difficult to judge to what extent expert advice was sought, but what is clear is that the Director of ICMR, Dr. Balaram Bhargava, and Dr. Vinod Paul of Niti Ayog supported and executed the directives of the PMO.

Interestingly, a wider debate was taking place among scientists in the media but neither the government or the ICMR engaged with these views. Few scientists and public health practitioners dared to speak critically of the government because of the political climate of intolerance to dissent. Among the few who did speak up was Dr. Gagandeep Kang who headed the National Immunization Technical Advisory Group. She was the only one to tender her resignation from her position and cited personal reasons for doing so. In several interviews to the media following her resignation, she was outspoken and discussed the limits of a lockdown approach to the pandemic especially in light of the crisis of migrants. She highlighted the importance of behavioral change at the population level, especially when there was no effective therapeutic intervention and vaccines were still at an early stage of development. In an interview Dr. Gagandeep Kang expressed that:

“I think one thing that we don’t do well in public health is look at behavior change – what are the drivers of behavior change across the population and [of] sustained behavior change? That actually requires a lot of effort and there are many people who are specialized in doing that. It requires an investment in investigating what matters to people and crafting your messages around making sure that this is shown to be a benefit to you. We are not doing that” (The Wire, November 19th 2020).

The retired leading epidemiologist, Dr. Muliyel, from Christian Medical College, Vellore also questioned the need for a stringent lockdown and suggested that given the paucity of services, the best way forward is to allow exposure of the disease to the younger population in order to build herd immunity. In an interview for the The Print he stated that:

“Lockdowns may flatten the curve but cannot completely stall the infection, even if those with flu-like symptoms are separated and quarantined. COVID-19 virus will be active in those who remain asymptomatic, and hence undetectable unless more people are tested. Once these restrictions go with lockdowns lifted and people interact with each other, the virus can make a reappearance and restart the transmission (The Print, April 15th 2020).

The politics of vaccine development and its roll out

Given the lack of an efficacious therapeutic intervention, there was a broad consensus within the public health community for a vaccine that would break transmission of infection and prevent severity of illness and death due to COVID-19. The government support for vaccine development was in the form of a public-private partnership – between Bharat Biotech, a company based in Hyderabad, ICMR and the National Institute of Virology – to develop a vaccine that has been named Covaxin. The Serum Institute in Pune, the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer, was part of the Oxford University-Astra Zeneca trials, and a partner in developing the vaccine dubbed Covishield. The government was keen to fast track the approvals and production of the vaccines. The scientific and ethical approvals were accelerated and Phase 1 of the trial for Covaxin was started in July 2020. Meanwhile, the ICMR director issued a letter asking the institutions involved in the trial to speed up their process of ethical clearances in order to allow for the announcement of the vaccine by the Prime Minister on August 15, India’s Independence Day.

The scientific community was critical of announcing the readiness of the vaccine without adhering to the necessary protocols of a clinical trial. In my view, this was once again an example of politics dictating science. The government wanted to showcase to the world the ‘Made in India Vaccine’ with little consideration for observing standard protocols. There was much political mileage to be made from this decision, which was defended by loyalist scientists.

The decision for an emergency roll out of the Covaxin without the Phase 3 trial data for assessing its efficacy and safety was controversial. The scientific community was critical of announcing the readiness of the vaccine without adhering to the necessary protocols of a clinical trial. In my view, this was once again an example of politics dictating science. The government wanted to showcase to the world the ‘Made in India Vaccine’ with little consideration for observing standard protocols. There was much political mileage to be made from this decision, which was defended by loyalist scientists. The ‘Made in India Vaccine’ became the pride of India’s nationalism and the centerpiece of the Prime Minister’s slogan of Atmanirbhar Bharat (Self Reliant Bharat). The vaccine was donated to several South Asian countries, consistent with building a brand image of India as a rising global power. The political agenda was progressing while several doctors and frontline workers were simultaneously questioning the efficacy and safety of Covaxin. Reports suggest that there was vaccine hesitancy around Covaxin while the government hyped the success of the vaccination roll-out.

In the present climate where there is growing intolerance by the government for dissenting views, scientific debate and dialogue have suffered a setback. The COVID-19 pandemic in India has shown how science has become a pawn to further the project of nationalism with the support of loyalist experts.

While several scientists privately questioned the evidence that was being used by the government to make such important decisions, many within leading scientific institutions chose to remain silent. This was largely due to fear of being victimized from within their respective institutions and by the government. Apart from the medical and public health community, several economists and activists were using media platforms to openly question the government’s decisions. In the present climate where there is growing intolerance by the government for dissenting views, scientific debate and dialogue have suffered a setback. The COVID-19 pandemic in India has shown how science has become a pawn to further the project of nationalism with the support of loyalist experts.

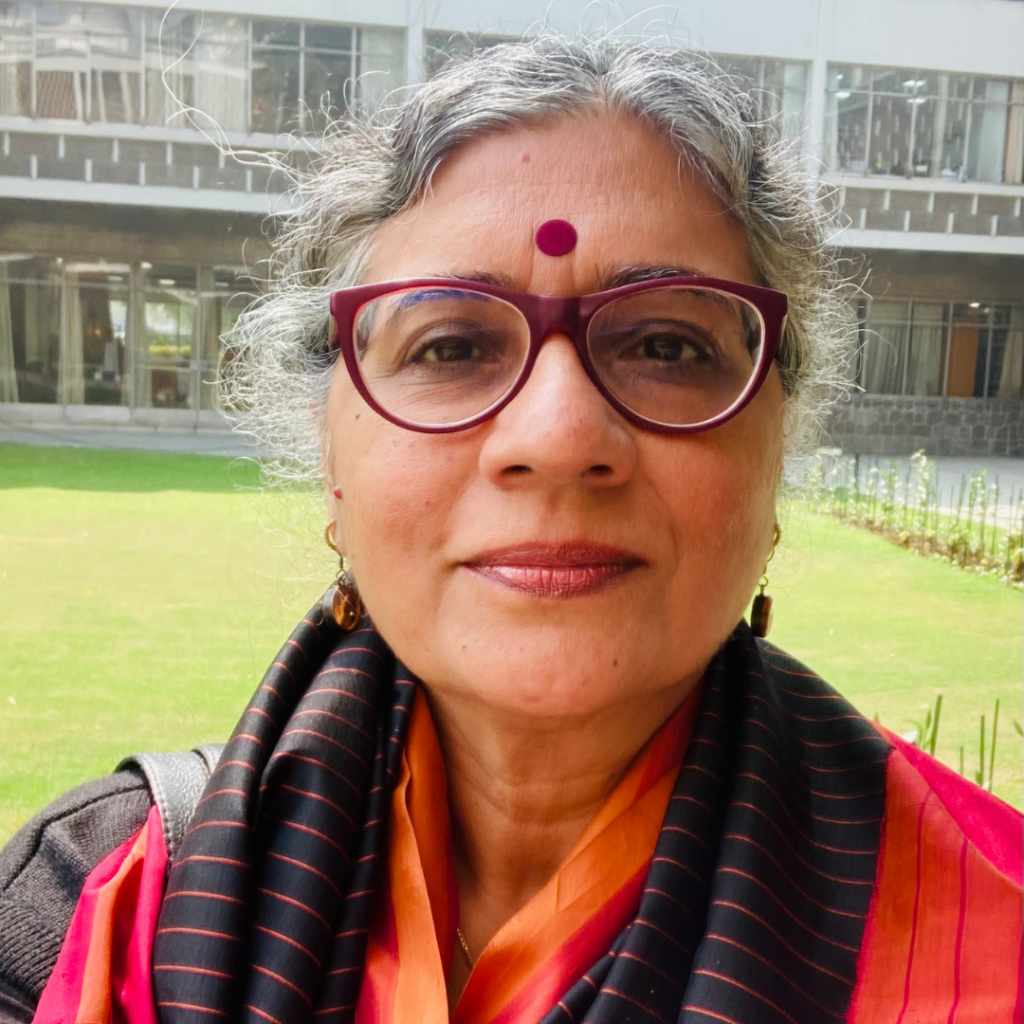

Dr Rama Baru. is a professor at the Centre of Social Medicine and Community Health, Jawaharlal Nehru University. She is an honorary fellow with the Institute of Chinese Studies and honorary professor at India Studies Centre, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China. Her research focus is on social determinants of health, health policy, international health, the privatization of health services and inequalities in health.