Questions of gender loom large in visual representations of the pandemic response and public health campaigns in Shenzhen. Mary Ann O’Donnell provides an account of how gender and animation are employed on social media by the public and state authorities as part of this campaign.

“Big Whites (大白)” are the omnipresent and seemingly omnipotent figures of China’s 2022 lockdown, so named for their white full-body hazmat suits. Big Whites have been the Chinese government’s social interface for managing the Omicron outbreak. Big White teams consist of medical workers, police officers, community office representatives, and volunteers who come (as the government repeatedly emphasizes) from all walks of life. In their capacity as service providers, Big Whites conduct COVID tests, deliver food to residents in locked-down buildings, and coordinate other public services within a designated area. However, Big Whites are also the public face of COVID security. They conduct building sweeps for testing holdouts, they act as gatekeepers at locked-down estates and neighborhoods, and they patrol locked-down areas to ensure everyone else is in their homes.

The moniker “Big White” has a double origin story. First, it derives from the gear that the management teams wear. In addition to being fully masked, hands are gloved and shoes are covered. There is a turquoise blue stripe which runs along suit seams and some Big Whites have personalized their suits with magic marker inscriptions. Second, “Big White” is also the Chinese translation for the plus-sized inflatable healthcare robot named Baymax, a character from the 2014 Disney film Big Hero 6. In the film, Baymax teams up with 14-year-old robotics prodigy Hiro Hamada to save their hometown San Fransokyo from an evil supervillain. Baymax and Hiro team up with four other nerds to form a band of high-tech warriors against evil uses of technology especially biotech. (Image 1)

Big Whites conduct COVID tests, deliver food to residents in locked-down buildings, and coordinate other public services within a designated area. However, Big Whites are also the public face of COVID security.

In a 23 March post on the English language WeChat account, EyeShenzhen, author Li Dan explained the connection between pandemic work teams and an animated film: “Chinese netizens use it [Big White] as a nickname for frontliners who are fighting the COVID-19 pandemic because they wear white protective coveralls on the job, and they work selflessly to protect the safety of the public.”

This essay touches upon two interrelated issues in the social media representations of Big Whites in Shenzhen—the gender of caregiving and the role of animation in conceptualizing pandemic management.

Image 1: Fan art of Hiro and Baymax from Fanpop, a website which hosts fan art and fiction

The Gender of Caregiving

During the height of the Shenzhen outbreak (February and March 2022), all levels of the Shenzhen government promoted Big Whites as hardworking, warmhearted, and cute. For example, in a 6 March post titled “‘Big Whites,’ You’ve Gone Above and Beyond (“大白”,你们幸苦了),” the Futian government figured Big Whites as an expression of public spirit, emphasizing that they represented ordinary Shenzheners—nameless heroes of the pandemic. Nevertheless, the post itself humanized Big Whites, allowing Shenzheners to see the people behind the hazmat suit. In practice, humanization was achieved by emphasizing these Big Whites’ big beautiful eyes, highlighting how Image 1, Fan art of Hiro and Baymax from the website www.fanpop.com, which hosts fan art and fiction. Cute—indeed non-threatening—they were (Images 2, 3, and 4, below). Unsurprisingly, these cute representations were young women.

Images 2, 3, and 4 (left to right): Exhausted Big Whites resting at night; two sisters who served as a delivery driver and a nurse, respectively; a drawing of Big Whites.

The feminization of Big Whites as cute caregivers is part of a wider Shenzhen gender discourse about relationships with women from whom different kinds of care are expected. Throughout China, fictive kin is a way of transforming strangers into acquaintances and friends through idealized understandings of kin relationships. There are three generations of kin terms at play in Shenzhen’s Big White discourse. For instance, ‘Grandma (奶奶)’ is a term of respect which comes with the expectation of unconditional love from her and gentle care from the ‘grandchild.’ Middle-aged women are referred to as ‘Auntie (阿姨)’ to their face and sometimes ‘Old Mom (大妈)’ behind their back. Auntie is the more complex of the two and is used both as a term of respect for women a generation older than the speaker and as a moniker for middle-aged women who work in low-paid service jobs, especially (and emblematically) janitorial services. In contrast, Old Mom is usually used to describe annoying older women with enough social clout (like one’s actual mother) that they must be treated with respect despite their nagging and/or public dancing to dated music.

Within one’s own generation there are ’Older and Younger Sisters (姐妹).’ Older Sister is the affectionate and more significantly the non-sexualized nickname for friendly relations between people of the same generation while Younger Sister is used for younger women who provide unquestioning and often sexualized service. Cross-generational use of these terms comprises transgression of expected norms, such as when an older man refers to a younger woman as Younger Sister or when people disparage a young man by saying he’s dating an Older Sister. The cute Big Whites exemplify the idealized Older Sister.

The feminization of Big Whites as cute caregivers is part of a wider Shenzhen gender discourse about relationships with women from whom different kinds of care are expected.

In contrast to the feminized images of caregiving Big Whites, Disney’s re-imagineered Baymax (based on a Marvel comic) may be huggable but uses masculine pronouns. Moreover, like the Marvel version, the Disney Baymax is a robotic synthformer, meaning he has a default as well as a hero form. An important difference between the Marvel and Disney versions of Baymax, however, is their relationship to caregiving. Whereas the Marvel Baymax was designed to serve Hiro’s daily needs, he was nevertheless programmed for violence—to defend the helpless and secure retributive justice. His hero form is hyper-masculine and threatening. In contrast, Disney Baymax is a health and emotional support robot programmed to detect and respond to the needs of those nearby. In his hero form Baymax is covered by a hard red armor and has wings and detachable fists, appearing noticeably stronger than his default form. This further strengthens the symbolic connection between masculinity and heroism in Big Hero 6 even when heroism takes the form of caregiving and restorative justice (Image 5).

Image 5: Baymax and Hiro’s respective hero forms by Jazmine Ibarra

Animated Caregiving in Shenzhen in 2022

In her ethnography of animation in and from technocratic Taiwan, Teri Silvio (2019) argues that globally we are shifting from a politics of embodied performance to one of animated representation. She defines this as: “The construction of social others through the projection of qualities perceived as human—life, soul, power, agency, intentionality, personality, and so on—outside the self and into the sensory environment, through acts of creation, perception, and interaction.” (19)

Image 6 illustrates how Big Whites were treated as comic book characters on Shenzhen social media. The text reads, “Shenzheners have humble wishes: to be able to go home when they leave the office and to be able to sleep until dawn without being woken up by a loudspeaker [calling them for emergency corona testing].” Through the logic of animation, this image projects a willingness to suffer, earnestness, and empathy for Shenzheners onto default male Big White characters regardless of who is under the suit.

The redeployment of Olympic mascots Bing Dundun (冰墩墩) and Xue Rongrong (雪容融) in Shenzhen’s mass testing campaign illustrates the narrow definition of animation (Image 7). Although Bing Dundun and Xue Rongrong are clearly not alive, they were nevertheless perceived as being so, with warm personalities, patriotic emotions, and strong affection for Shenzhen. In turn, they modeled a particular way of being during the pandemic as Shenzheners could imagine themselves and their relationship to the city through Bing Dundun and Xue Rongrong.

Presently, these representations of Big Whites reveal how gender informs everyday life in Shenzhen under grid management.

Two other examples of how animated characters represented the pandemic in Shenzhen were the ‘Green Horse (绿马)’ and the ‘Ding Dong Chicken (叮咚鸡)’ (Images 8 and 9). Crucially, unlike Bing Dundun and Xue Rongrong, the Green Horse and the Ding Dong Chicken were locally produced digital stickers which went viral. They coded residents’ desire for mobility and reflecting uncertainties over when the lockdown would be lifted generally as well as when specific buildings and neighborhoods would be reopened.

Images 7, 8, 9 (left to right): Bing Dundun and Xue Rongrong sticker from mass testing in Xili Subdistrict; the ‘Green Horse,’ a pun on the Mandarin for ‘Green Health Code (绿码),’ which was a prerequisite for even limited mobility in the city under lockdown; the Ding Dong Chicken, a pun on the Mandarin expression ‘wait until notification (等通知).’ Interestingly, while Green Horses and Ding Dong Chickens proliferated on Shenzhen social media, Bing Dundun and Xue Rongrong’s appearances featured primarily on official media.

In this narrow sense Shenzhen’s Big Whites were not animated characters. There were, after all, real people beneath the hazmat suits. On the ground, specific people wore hazmat suits to perform assigned tasks. On social media, however, both official WeChat accounts as well as individual user accounts’ images of Big Whites portrayed them as if they were comic book characters. Visually, they were placed in frames, their thoughts displayed in bubbles, and given captions to express a range of emotions (Images 6, above). Moreover, the default gender of Big Whites was male, especially in stickers and emoticons which were either generalized representations of society or showed them performing specific acts such as making deliveries, crossing cordons, and gatekeeping (Image 10 and 11). In addition, the government and its representatives actively promoted the creation of ‘fan fiction’ about and for Big Whites as exemplified by image 5 above.

Images 10 and 11: the default gender of Big Whites was male, stressing that they were ‘lawyers, inspectors, firemen, traffic uncles’—a representative selection of Shenzhen society who were cooperating with health professionals to achieve Zero-COVID, or highlighting them as active heroes.

Preliminary Thoughts on the Animated Pandemic

Even as Shenzhen transitioned from strict to slightly relaxed management protocols, the failure of the same program in Shanghai revealed a third feature of Big Whites as animated characters—a hidden evil form which can emerge in particular contexts. Videos and photographs of Big Whites forcibly detaining older people, killing pets, and acting as guards at COVID camps (方舱医院) in Shanghai abruptly revealed this previously hidden form. Certainly, this narrative structure of a beautiful or benign exterior form masking an evil form is a trope common in animation. In fact, Robert Callaghan, the villain of Big Hero 6, is head of a robotics program at San Fransokyo Institute of Technology and first appears in the story disguised as a genius professor who feels compassion for marginalized nerds. Moreover, it is the appearance of this latent form that allows audiences to interpret whether a character is to be understood as either good or evil.

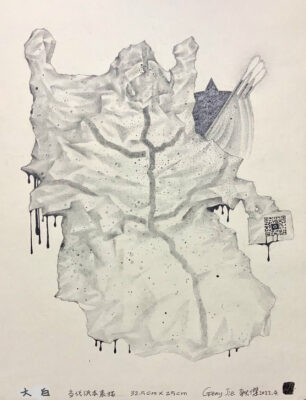

The narrative logic of animation not only enables the anti-social actions of Big Whites to be easily understood within the dialectic of default and hidden forms, but also labels violence, price gouging, and abuse as part of a larger narrative of good versus evil where unveiling hidden forms is an important element of social media discourse. In April, for example, Shanghai artist Geng Jie began work on a series of drawings which called attention to the hazmat suit as an external form which masked the alternative—but more ‘real’—essence of the Big White as a social character (Image 12).

Image 12: “Big White” by Shanghai artist Geng Jie (耿杰)

Presently, these representations of Big Whites reveal how gender informs everyday life in Shenzhen under grid management. On the one hand, everyday caregiving in Shenzhen remains feminized. On the other hand, the use of Big Whites and testing protocols to control population movements have been standardized as masculine. Moreover, these gendered functions are invisible to the eye. Instead, a Big White’s hidden form—a caring “female” or an authoritarian “male”—is only revealed in specific contexts.

WeChat Accounts Cited:

EyeShenzhen WeChat ID: eyeshenzhen.

北京友谊医院 WeChat ID BFH1952

大神有空 WeChat ID: gh_36f8009052f8

深圳卫健委 WeChat ID: szwjwwx

幸福福田 WeChat ID: happyfutian.

Mary Ann O’Donnell is an artist-ethnographer who lives in Shenzhen. Ongoing projects include her blog, Shenzhen Noted, and the Handshake 302 public art project. In 2017, the University of Chicago Press published “Learning from Shenzhen: China’s Post-Mao Experiment from Special Zone to Model City,” a volume she co-edited.