China’s Yunnan province is widely known for its diversity and multiplicity of communities. While these communities have had extensive historical relations with successive Chinese dynasties, the most recent form of Chinese nationhood under the government of the People’s Republic of China has brought new legal, administrative and constitutional frameworks to the region. These frameworks raise several questions about how these communities are classified, and how they negotiate this identity; how these classifications compare with those of other nation states with minority communities; and how these frameworks both transform and reflect the historical relations between Han and non-Han communities in China.

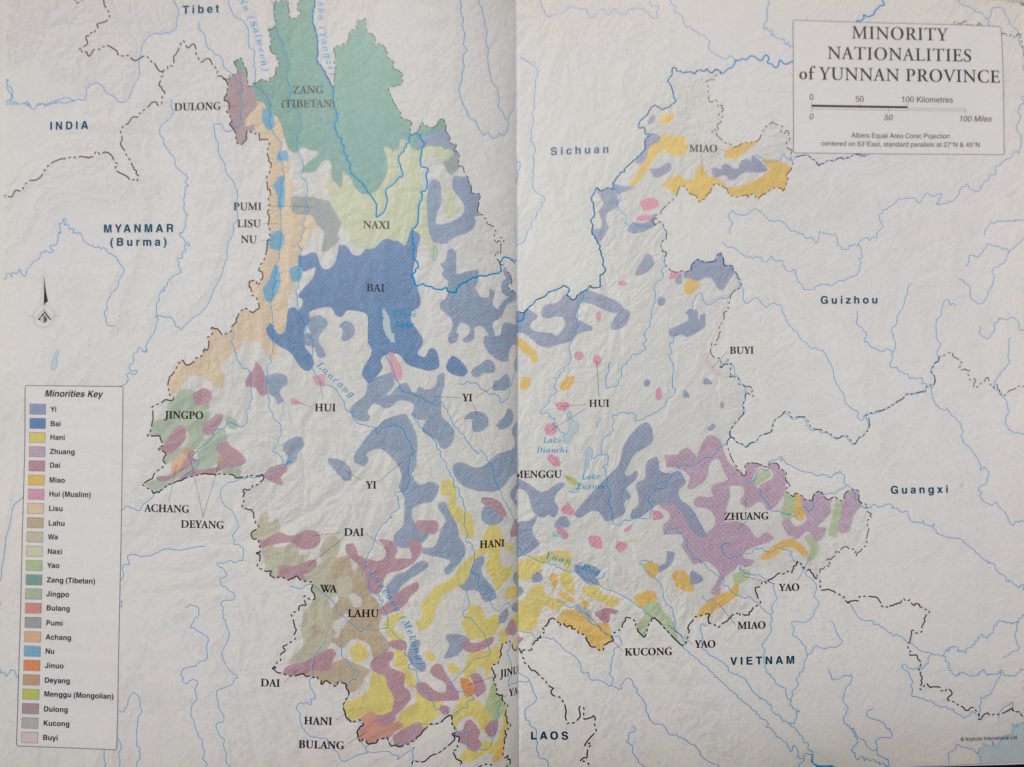

The Han Chinese are roughly 92 percent of the Chinese population[i], but in Yunnan, they account for about 66 percent[ii], making Yunnan one of China’s most diverse provinces. Classified by the government as “minority nationalities” or shaoshu minzu (in Chinese), non-Han communities make up the remaining 34 percent of Yunnan’s population. The study of how contemporary nation states negotiate minority identities within their borders is therefore especially significant in Yunnan, where historical relations between the Han Chinese and non-Han minorities have taken on a new significance through the mechanisms of the Chinese nation state, and the ways in which these mechanisms compare with global efforts to recognize diversity and minority rights.

These comparisons are especially insightful within the international academic and political discourse of indigeneity, where specific laws, declarations and narratives have been adopted by the international community to safeguard the rights of indigenous communities[iii]. From a comparative perspective, it is also significant that both India and China adopted the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in 2007, while both nations maintained that they are not required to uphold the safeguards of the declaration for its citizens.

India, for its part, considers “the entire population of India at Independence, and their successors, to be indigenous”, while also claiming, at an earlier meeting at the UN, that there are “no indigenous peoples in India and that tribals did not constitute what is understood here by the term ‘indigenous populations’”[iv]. Similarly, while it acknowledges indigenous rights elsewhere, China does not recognize the term ‘indigenous peoples’ within its own borders[v]. While many advocacy groups have pointed out that these arguments effectively absolve both countries of their commitment to apply the safeguards of the declaration, part of my research focuses on uncovering whether notions of indigeneity persist nevertheless, in popular and local discourse, if not at an official level.

In India, for example, the word “Adivasi” is widely used to refer to many communities that would be considered indigenous by international advocacy groups. In English, the word roughly translates into “early inhabitants” or aboriginal. The widespread acceptance of this word, but the official resistance to the idea of indigeneity, indicates a tension between local experience and popular narratives, and the discourse taking place globally, both within the international community and academic and activist communities.

I intend to explore whether similar notions of indigeneity are present in Chinese popular discourse and local culture, and how the category of “indigenous” differs from the Chinese state’s category of “minority nationality”, as both are mechanisms designed to account for diversity and difference within nation states. While the notion of indigeneity has been applied to minority communities in China through the work of international organizations, especially with regard to Tibetan and Uighur communities, I intend to look more widely at the other minority nationalities in Yunnan, a province where 25 of the 55 officially recognized minorities live.

As a visual artist with a background in research and advocacy for indigenous communities in India, my project will be interdisciplinary and will rely on visual, audio and text based documentation. My preliminary research has consisted of conversations with scholars and travelers who have visited or lived in Yunnan, and who are familiar with the administrative structure of the Chinese state, as it relates to minority nationalities. Much of my initial research has also brought up texts by advocacy groups, which view the situation in China through the usual lens of indigeneity, and the histories and narratives that this implies. I would like to examine whether these narratives play out in the same way in the Chinese context as they would for other, officially accepted, indigenous communities, such as those in the Americas. My research will include visits to the capital city of Kunming, and from there to Dali, Lijiang and finally, to Zhongdian County, officially renamed Shangri-La in 2001, in eastern Tibet.

[i] http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/07/08/AR2009070802718.html?noredirect=on

[ii] https://www.gokunming.com/en/blog/item/3769/yunnans_population_by_the_numbers

[iii] https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/about-us.html

[iv] As cited in Aufschnaiter (2007:34) http://othes.univie.ac.at/1105/1/Aufschnaiter_Diplomarbeit.pdf

[v] https://www.culturalsurvival.org/sites/default/files/UPR%20Report%20China%202017%20%20.pdf