By Joseph Wheeler, 8/2/2014. All forms of media representation are simplifications of a real world object for the sake of conveying information. From maps, to icons, to photographs and even language, representations serve to summarize something in order to convey complex information in a concise and understandable way. Without representations conversations would be completely impossible; we could have no shared understanding of objects in reality. However, as necessary as they are there is a potential danger when our created representations are presented as fundamental truths—especially when dealing with representations of groups of peoples.

A stereotype is a specific representation that is created, intentionally or unintentionally, to affiliate groups of people with predetermined characteristics. A stereotype works to limit the range of characteristics that one assumes is possible for a certain type of person. Whenever you see someone who you affiliate with that group of people you will assume they are characterized by the facets of that stereotype. This fixing of meaning is detrimental to both the cultural perception of that group, as well as those individuals’ self-image and conceived potential. Presenting limited representations of groups of peoples via tropes or stereotypes—whether that is along the lines of race, class, nationality, gender, or sexuality—begins to blur the line between perception and reality, effectively redefining how the viewer understands the world around them.

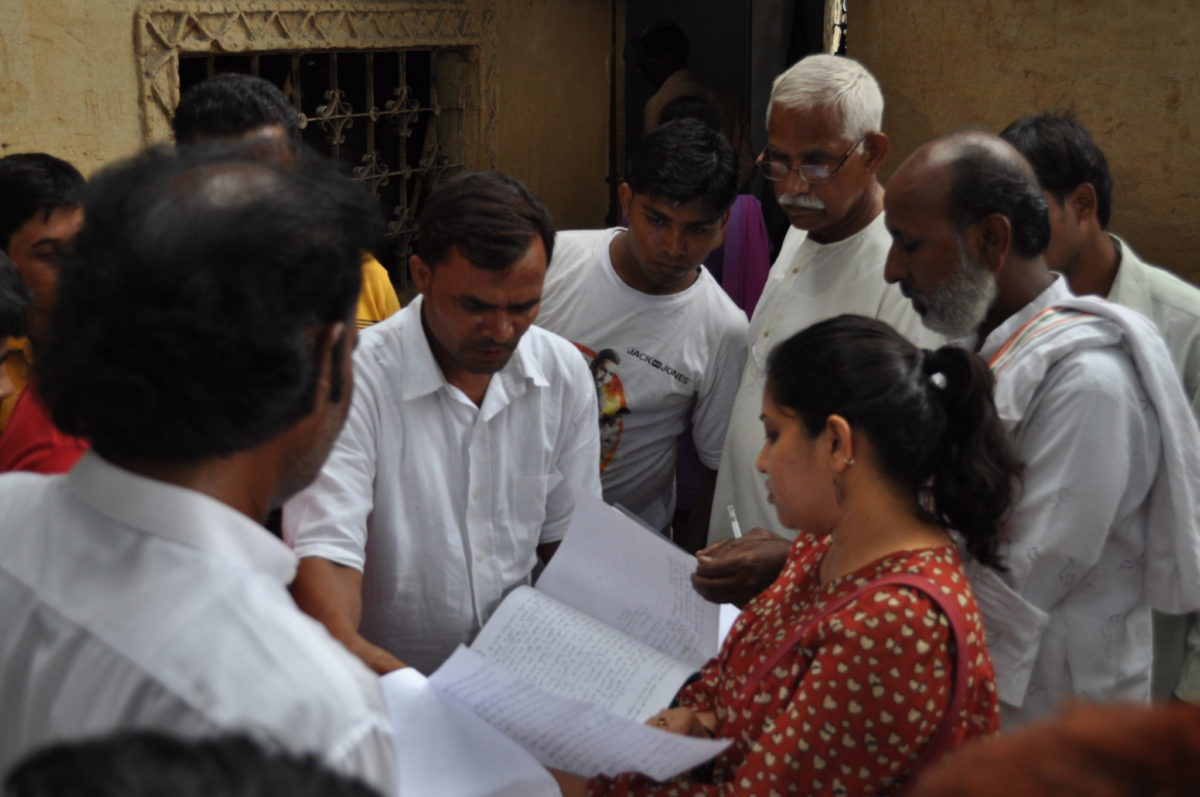

When working with international advocacy media, like I am with Nazdeek as part of my ICI fellowship, it is important to be aware of the representations that are being presented to the rest of the world, and to avoid falling into the same old stereotypes that might affect others’ perception of the people we are working with. For example: I had the opportunity to visit the Kathputli Colony earlier this week. Kathputli Colony is an informal housing settlement in Delhi that is scheduled to be demolished as part of a slum clearance/urban redevelopment plan by the government. While it definitely fulfilled many of the stereotypical characteristics of a Delhi Slum that I had been exposed to, I was surprised to find a community of individuals who were proud of their homes, and passionate and informed about their rights—some of who have even been to Europe, Canada and the US. Even more inspiring was the pride they held for their professions; Kathputli is Hindi for “puppet” and most of the residence are puppet makers, wood-carvers, musicians, or street-performers. While the label of slum-dweller might be applicable, these individuals had far more interesting stories to tell than the images that simple stereotypes might initially invoke.

Representations, especially if they are meant to empower those they represent, need reveal the complexity of any given social issue, acknowledging the aspects of a stereotype that might be valid while be nuanced enough to reveal that individuals have far more depth than what stereotypes present. Moving forward, as I work to develop media projects for Nazdeek regarding slum clearance, maternal mortality, and fare wage I need to be wary of the ways in which the people Nazdeek are working with are being represented to the rest of the world. These projects have a lot of potential to raise awareness about the issues Nazdeek is addressing, while simultaneously advertising their amazing work, but they carry the heavy responsibility of mindful representation. This will be a great challenge, but is something I am thrilled to have the opportunity to be spearheading for the organization in the weeks to come.